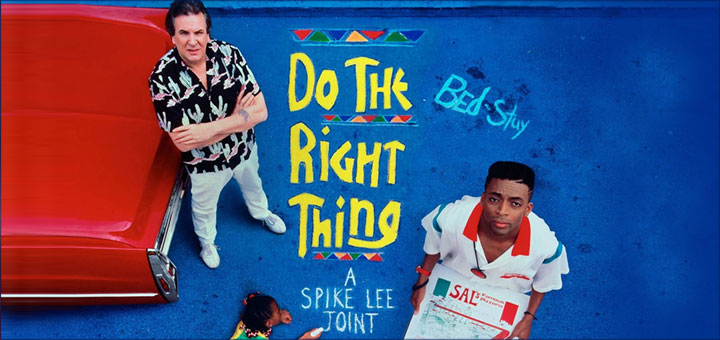

Do the Right Thing is a perfect companion piece to our upcoming feature, Twelve Angry Men. Sidney Lumet’s not-quite-a-courtroom-drama is set in a single afternoon on the hottest day of the year in a jury room in Chicago in the 1950s. Spike Lee’s urban opera is set over 24 hours on the hottest day of the year on a single block in Brooklyn in the late 1980s. Both films depict growing intensity and heat – climatic, emotional and political – in a claustrophobic atmosphere where tempers fray and passions become inflamed to boiling point and beyond. To conflict.

Spike Lee’s work is overwhelmingly concerned with race, emancipation and exposing complex societal problems. His production company, founded in 1979 when Lee was 22, is called 40 Acres and a Mule – a reference to the paltry “reparations” settlement given to emancipated previously-enslaved persons after the US Civil War. Blackness and racialised otherness loom large in all his films, all the way from his 1986 debut, She’s Gotta Have It, to his 2025 documentary series about the devastation of New Orleans, Katrina: Come Hell and High Water.

Critical responses to Do the Right Thing varied, especially among white writers. Roger Ebert, probably the most famous American film critic, named it his number one film of 1989. David Denby, on the other hand, wrote that: “If Spike Lee is a commercial opportunist, he’s also playing with dynamite in an urban playground. The response could get away from him” – stopping just short of accusing him of trying to incite a riot. White fears that Do the Right Thing could ignite the flames of racial violence – especially in a New York torn apart by crime and interracial violence – were very, very real. Lee rightly responded that Black audiences could tell the difference between an incitement to violence and a piece of art and that to suggest otherwise was deeply racist.

During the 1990 Oscar ceremony, while announcing the Best Picture nominees, Kim Basinger ignored her scripted text to say: “We’ve got five great films here, and they’re great for one reason: because they tell the truth. But there is one film missing from this list, that deserves to be on it, because ironically, it might tell the biggest truth of all, and that’s Do the Right Thing.” She caught flak from the Academy for that, but she was absolutely right. The Best Picture winner that year was Driving Miss Daisy. And the film you are about to watch will demonstrate why that decision was not only wrong, but also insulting.

Do the Right Thing did not, in fact, incite a riot. But it very nearly predicted one: less than two years later, Rodney King would be beaten senseless by members of the LAPD on camera during a routine traffic stop. King was intoxicated and, unaware they were being filmed, the officers falsely accused him of resisting arrest and bludgeoned him almost to death. Local resident George Holliday recorded the incident from his balcony and sent the footage to a local news station, and its airing led to a wave of uprisings across Los Angeles County by a community sick to breaking point of police brutality, systemic racism and disenfranchisement.

Lee’s films are characterised by excess – a term borrowed from psychoanalysis that refers to a disruption of the social order by means of intense passion and the expression of individuality – and near-catharsis.

But the first thing that strikes one about Do the Right Thing is the mise-en-scène – a theatrical phrase that simply means what you see on the screen – so props, sets, backdrops, costume. (The other elements of film style are lighting – how we see things – cinematography – the angle from which we see them – and editing – which determines the order in which and speed with which we see things – or, more importantly, how they are shown to us.)

The colours are bright – the primary colours of the Pan-African flag, of designer-label sports gear, of eighties fashion. Ernest R Dickerson, the cinematographer, brilliantly portrays the excessive temperatures of high summer in New York using multiple arc lights in addition to the garish palette. This gives the film a heightened realism – the heat radiates off the screen, the characters swelter and stew and you feel as if you are there.

This is entirely deliberate. Lee wants you on edge, and achieving it is one of his many great talents as a filmmaker. White audiences often find Lee’s films threatening and divisive. In particular, Do the Right Thing and Malcolm X are elating – you know you’ve just watched something impressive – but discomfiting, forcing us to confront notions of blackness and whiteness, community and segregation, gentrification, interracial conflict and, crucially for me, why what we have seen is so unsettling, so confronting, to us. This isn’t the way that Hollywood usually deals with race – it’s not how white Hollywood ever deals with race. There is no room in such sanitised narratives for portrayals of disempowered resentment, thwarted masculinity, anger or human frailty. The big, famous films about race that came before – The Colour Purple, To Sir With Love, Lilies of the Field, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Mississippi Burning, Glory – mostly feature “acceptable blacks” (an urbane Sidney Poitier meeting Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy as the parents of his white fiancée, for example) – and involve a kumbaya coming together of the races at the end of the story, usually thanks to the largesse or courage of a white saviour character. Without spoiling too much, Do the Right Thing offers no such catharsis.

To understand Do the Right Thing, one must also understand something of hip hop culture, which infuses everything, from the themes to characters’ clothing to the graffiti, the dialogue, the music – Public Enemy wrote their biggest hit, Fight the Power, for the film – and Rosie Perez’s fevered, uncomfortably protracted dance over the opening credits.

Hip hop is about more than just rap music. It is a complete, self-contained culture. Its themes include Black pride, urban rage, frustration at all the bugs and features of a racist system, resistance and strength in community. Its primary art forms are MCing (what we tend to think of as “rap”), graffiti and street art, breakdancing, DJing and “knowledge” – an understanding of the culture’s history and principles.

Hip hop grew in response to the alienation of urban African Americans who grew up poor and dissatisfied with the lack of opportunity afforded them. As drug abuse, crime, destitution, under-education and under-employment flowed into communities, eroding them, hip hop was the release valve, the escape. The excesses of hip hop – brash brags about one’s prowess (sexual, professional and even criminal), a preoccupation with luxury commodities, a safe space to express strong emotions, especially rage and disappointment – provided a creative outlet for the tensions bubbling up in an ill society characterised by urban decay and institutional neglect.

It’s a common experience among disenfranchised urban populations of all races in many places that their neighbourhoods become gentrified – which I view as a kind of micro-colonialism. Your home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a suburb of Brooklyn, may be falling to pieces, but it’s yours. Then some hipsters move in, open an artisanal coffee shop on the corner where the youth centre or the public library – long closed due to underfunding – used to be. The hipsters pay slightly above market value for a loft three times the size of one in Manhattan or Queens, make some improvements and property values go up. Their friends visit, find it quaint, decide to move there as well. More fancy delis and boutiques move in, replacing the bodegas where people do their grocery shopping, forcing them to travel further to find affordable provisions or to spend beyond their means in their own neighbourhood. Rents go up as landlords realise they can charge the interlopers – usually white, affluent, educated – more money, pricing locals out of their homes. And so the neighbourhood becomes gentrified – not to the benefit of the people who have lived and loved and grown up in the area, but to their detriment as they are squeezed out and forced to move somewhere else, somewhere worse.

To return to Do the Right Thing, for all that it is an innovative departure from cinematic depictions of Blackness (traditionally told through a white lens), Spike Lee feels no apparent discomfort borrowing from the formal luminaries of film history. Visually he quotes everyone from Hitchcock to Orson Welles. His love of smash close-ups and montage editing put him solidly within the western canon of filmmaking.

He also borrows from Shakespeare and Greek theatre – the opening scene takes us past seven individual locations on a city block. Think of a Shakespearean comedy like Twelfth Night, which is usually staged so that every location can be seen on stage at once – Olivia’s estate, Orsino’s estate, the town square, the gardens in which Malvolio will stalk cross-gartered and yellow-stockinged in Act III – all are typically visible throughout the play. In Do the Right Thing the three old men on the corner – Sweet Dick Willie, Coconut Sid and their friend ML – are the Greek chorus, philosophising, narrating the action, giving us background and commentary on the people we are watching but not really getting involved in the drama themselves. That Lee eschews a post-cathartic resolution of order is crucial – here he deviates from Shakespearean norms and aligns himself with Plato and with Bertoldt Brecht, who both insisted that a drama that resolves itself in the final act is too comforting. The audience must be left with a sense of discomfort, of having unfinished business with the narrative they have watched unfold and a desire – a drive – to resolve things by effecting change themselves. Or it is all for nothing.

There’s even an element of Dickens at play in the characters’ names – they mark them not as types or stereotypes but archetypes. Sometimes these appellations are deadly earnest – Mother Sister, for example, is a god-fearing matriarch who disapproves of sin but despite her poverty has great empathy for those less fortunate than she. Sometimes they are tongue-in-cheek – as a drunk and a figure of fun, Da Mayor belies his lofty title, tragicomic in his gravitas and his cups. Radio Raheem – never seen without his boombox – represents youthful ebullience and creative freedom. His t-shirt reads “Bed Stuy – Do or Die” – both an homage to the neighbourhood and a grim foreshadowing of what’s to come. Buggin’ Out, a volatile, argumentative presence from his first appearance on screen, is someone who cannot keep his mouth shut if something bothers him, a man who never backs away from a fight but rather wades right in in defence of his wounded pride, his affronted dignity and even his pristine sneakers.

There are some big names of late-20th century Black, Latino and Italian American cinema here – Do the Right Thing was a launchpad for several illustrious careers including those of Lee himself, Rosie Perez, one Samuel L Jackson, Bill Nunn, Giancarlo Esposito and John Turturro. While most of these names may sound unfamiliar, you will recognise some of the faces – Turturro is beloved of the Coen brothers, while Esposito reached his career zenith playing drug kingpin Gus Fring in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. It’s also a swan song for several great actors – Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, who play Mother Sister and Da Mayor respectively, were real-life husband and wife, and in their younger days starred in the Broadway debut of Boesman and Lena. Danny Aiello, alumnus of many gangster films, plays Sal, the pizzeria owner.

In addition to the majority-Black cast, the film is shot through with symbols of Blackness and Black Pride. Medallions and leather jewellery fashioned in the shape of Africa signal a nod to the characters’ ancestry, heritage and repudiation of white, western norms. Team sports gear – the uniform of hip hop – is a vibrant reminder of the sole path to affluence most of these youth can imagine: sporting ability, fame, celebrity and sponsorship deals. The brightness of the clothing against the backdrop of urban decay, finding solace and dignity in decoration and self-expression.

Leave a comment