His Girl Friday began life as a Broadway play called The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur (both members of the Algonquin Round Table, a group of early 20th century New York intellectuals, and at least one of them a lover of Dorothy Parker’s). In the stage version, journalist Hildy Johnson makes one last farewell visit to the newspaper he works for before quitting to marry and settle down with his fiancée Jennie. Unwilling to lose his star reporter, Johnson’s scheming editor Walter Burns contrives to ruin Hildy’s romantic chances and lure him back to the newspaper game where he belongs.

Director Howard Hawks considered the play to have the “finest modern dialogue” ever written – so much so that he sometimes had guests at his parties read aloud from the script. It was at one such party, while a woman guest read the part of the reporter, that Hawks realised the play’s potential as a romantic comedy. Thus Hildy became a woman – not just any woman, but editor Walter’s ex-wife – and His Girl Friday, possibly the greatest of the screwball comedies, was born.

The film is perfect for watching now because, stylistically, it provides such a stark contrast to Do the Right Thing. Where Spike Lee breaks the fourth wall, having characters address the audience directly, and uses dynamic camera angles, smash close-ups and bright colours to convey liveliness, Hawks does the opposite. His framing is traditional, square; his palette black and white; he respects the implied proscenium arch separating the audience from the characters… Instead it’s the actors, the dialogue, the editing and the direction that keep the movie’s multiple juggling balls in the air.

I usually don’t show these films with subtitles (or at least put it to a vote beforehand), but for this one, we’ll be having subtitles on. The reason is that while most movies contain about 90 words of dialogue per minute of footage, His Girl Friday runs at an average of 240 words per minute, peaking at 300 words per minute in its most frenetic scenes. This velocity is one of the elements that make it a screwball comedy – a term for an unpredictable pitch that causes a baseball to move in an unexpected direction. The name was adopted for this subgenre of romantic comedy that emerged in the early 1930s, characterised by fast-paced, witty plots that often spoof traditional love stories and social conventions with a mixture of farce, slapstick and satire. They don’t tend to get made any more – the most recent example to get a wide theatrical release, 2003’s Down With Love, failed to revive the genre. The most famous screwball comedies share a lot of the same personnel – Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant starred in several, both together and apart, and directors like Howard Hawks and George Cukor made a living out of them (although they both made excellent films in other genres).

Film critic Stanley Cavell refers to His Girl Friday as a “comedy of remarriage”, positing this as a sub-subgenre of screwball comedies that includes The Philadelphia Story, Bringing Up Baby, It Happened One Night and Adam’s Rib (he also calls them “fairy tales for the Depression” because many of them take place against a backdrop of wealth, but that’s not so in this film’s case).

Hawks also contrasts heavily with Hitchcock – where Hitch’s filmmaking was stylised and frequently prioritised effect (usually to build suspense) over verisimilitude, Hawks displayed a slavish devotion to realism. He encouraged his actors to ad lib and develop “business” – physical habits that give depth and realism to a character, which wasn’t usual in the 30s and 40s. His players are restless and constantly moving – they fidget, they talk over each other, interrupt each other. When Hawks was asked if having actors step on each other’s lines didn’t come across as unnatural, he said: “Try listening in at a cocktail party sometime.”

He wasn’t wrong. There’s something completely naturalistic about the frenzied, breakneck dialogue in this film that snatches you up into its whirlwind. And there’s nothing boring about his classical approach – by using the tools and obeying the rules of classic Hollywood cinema, Hawks makes its artifice all but invisible.

The picture almost never stops moving – if the people in the foreground aren’t busy, those in the background are; if the camera isn’t moving with the actors, the edit is cutting between them, presenting the dialogue’s delivery in a classic shot-reverse shot format. People don’t sit or stand – they pace or perch on the corners of desks. When things momentarily grow quiet, it’s for a reason: something big is happening (or about to happen). The film is packed with reasons to hurry up – deadlines for newspaper copy, trains to be caught, executions in the morning. The only times Hildy and Walter settle down are when they’re together, comfortable and in sync – even if that takes the form of sniping at each other and, occasionally, outright physical violence.

It’s what makes them a great team. Hildy – Rosalind Russell – and Walter – Cary Grant – are not very nice people, but we root for them because they are smart, beautiful, dedicated, funny and so clearly made for each other. When Hildy arrives at the film’s opening to bid the Morning Post farewell, we know within moments that she’s not destined to finish up with her mild-mannered fiancé Bruce Baldwin, played by Ralph Bellamy. For all that Hildy calls Walter a snake, a double-crossing chimpanzee and “wonderful, in a loathsome sort of way”, it’s clear that they are cut from the same newsprint. They speak a common language, whether that’s the editorial language of newspapers or the intimate language of familiarity – meaningful looks, kicks under the table – and it signals their tribality and thus Bruce’s otherness. As Cavell writes, “They simply appreciate one another more than either of them appreciates anyone else, and they would rather be appreciated by one another than by anyone else. They just are at home with one another, whether or not they can live together under the same roof.”

It’s certainly not a feminist film, but for 1940, it’s a somewhat progressive one – locating a woman’s worth in her professional prowess rather than her marriageability. The battle of the sexes (another common theme in screwball comedy) ultimately isn’t “won” by the woman, but she goes happily enough to her defeat.

Do not look to this film, either, for a masterclass in journalistic ethics – in today’s landscape, Walter would be the ultimate tabloid hack, forgetting the credo that the press is supposed to report the news, not make it.

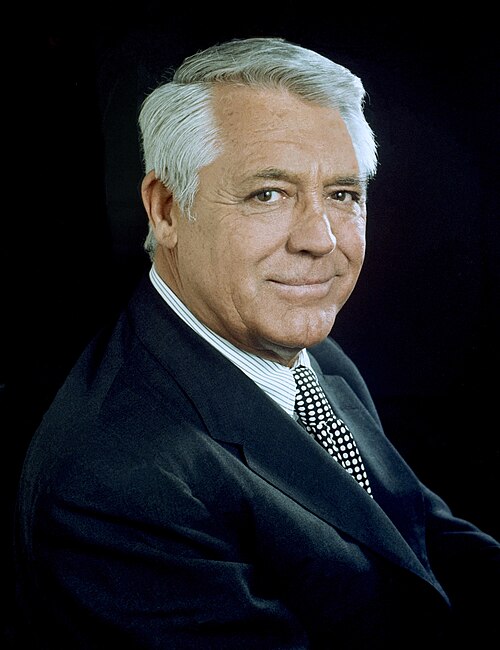

Although Rosalind Russell is the indisputable star of the film, I’d like to talk a little about Cary Grant, who had a greater impact on the overall Hollywood landscape. Born into poverty in Weston Super-Mare, near Bristol, Archibald Leach emigrated to the US at age 16 as a circus performer before changing his name to Cary Grant and making it big in Hollywood. He owed his big breaks to two risqué blondes whom the censors loathed: Mae West and Marlene Dietrich, both much bigger stars whose names drew audiences to his early work as their co-star.

It’s almost impossible to convey Grant’s contribution to the history of Hollywood. He was more than just the Brad Pitt or Robert Redford of his time – he epitomised the handsome matinee idol persona that became a staple of romantic comedies and heist capers for generations to come. Along with Katharine Hepburn and a handful of others, he is responsible for the trans-Atlantic manner of speaking adopted by film stars of classic Hollywood – that not quite British, not quite American accent that’s ubiquitously representative of the era. Suave and urbane, Grant had what critic William Rothman called “a distinctive kind of nonmacho masculinity”. He so embodied the romantic hero of the period that when Billy Wilder’s gender-bending comedy Some Like It Hot called for Tony Curtis to conjure up the type of man with whom Marilyn Monroe could plausibly fall madly in love, Curtis simply impersonated Grant wholesale – and nailed it.

Grant’s reputation preceded him to such a point that it rather overshadowed the man himself. He struggled throughout his life with depression, becoming a proponent of talking therapy and, later, in the 1960s, of therapeutic LSD. He was witty in interviews, but his pithy responses sometimes revealed just how disconnected Archie Leach the man felt from his Cary Grant public image. When one interviewer gushed that “Every man wants to be Cary Grant,” Grant responded, “Hell, even I’d like to be Cary Grant!” After he’d retired, a journalist sent a fact-check telegram asking “HOW OLD CARY GRANT”, only to receive the reply “OLD CARY GRANT FINE. HOW YOU?”

On a trivia note, John Cleese was also born in Weston Super-Mare and found Grant’s birth name so hilarious (and so incongruous with Grant’s charm) that he made it his character’s name in A Fish Called Wanda – which was probably the last successful screwball comedy ever made.

You’ll also encounter the term “mashing” in His Girl Friday – this was a misdemeanour equivalent to catcalling, basically propositioning a woman in public.A film with a 190-page script would usually have a running time of just over three hours. His Girl Friday is 92 minutes long. So, try and keep up!

Leave a comment