Ealing Studios and postwar British cinema

Plot summary: Louis Mazzini is the son of a penniless Italian opera singer and a young noblewoman whose family, disapproving of her choice of husband, had disowned her. When they refuse her dying wish – to be buried in the family cemetery – Louis determines to do away with everyone who stands between himself and the Dukedom of Chalfont.

Kind Hearts and Coronets is number five on the British Film Institute’s list of the greatest British films.

When we talk about classic film, the tendency is to adopt the Great Man of History narrative. We talk about oeuvres and auteurs — a Scorsese film, a Spike Lee joint, Billy Wilder’s body of work; we even add adjectives like “Hitchcockian” and “Cronenbergesque” to our lexicon. But when we talk about the Ealing Comedies, they are so specific to a time and a place (London in the wake of the Blitz of WW2) that the identities of some really great directors — including Robert Hamer, who directed Kind Hearts and Coronets, and Charles Crichton, whose last work half a century later would be to collaborate with John Cleese on 1988’s Oscar-winning A Fish Called Wanda — are eclipsed by the legend that is Ealing Studios itself.

Ealing Studios was built in 1902 and adapted for sound in 1931 — and films and television are still being made there (including the inexplicably popular Downton Abbey). It is the oldest continuously working studio facility for film production in the world. Many notable films were shot at Ealing after the advent of sound cinema, but its heyday as the centre of the British film industry was the 40s and 50s. In 1955 it was sold to the BBC, whereafter it became home to the likes of Monty Python, Porridge and The Singing Detective.

Between 1947 and 1957, though, a run of quintessentially British comedy films was made here, including Kind Hearts and Coronets (with location shooting at Leeds Castle in Kent). The Ealing Comedies are at least partly responsible for what came to be known as the British sense of humour. The sardonic nature of the Ealing Comedies influenced everyone from the Goons to the Pythons and beyond. In fact, a very young Peter Sellers has a small role in The Ladykillers, the last great comedy of the Ealing era.

Kind Hearts and Coronets itself is ironic, unglamorous, darkly comic and obsessed with class – all themes and traits with which many postwar British films are preoccupied. They’re steeped in the gallows humour and cynicism of a country putting itself back together after the privations of World War Two, only to find that the class system, which had by necessity relaxed somewhat during wartime, had snapped back into place with the onset of peace. Louis’s vendetta against his mother’s clan, which he claims is revenge for their rejection of her, seems to be motivated equally (if not more so) by social jealousy – resentment at having been born lower-middle class and not an aristocrat. The stately Edith herself asks, at a pivotal moment in the film, “Was Lord Tennyson far from the mark when he wrote, ‘Kind hearts are more than coronets, and simple faith than Norman blood?’” – musing on whether nobility is blood-borne or the product of a person’s character.

Although it’s set in the Edwardian era, long before the class-conscious, upwardly mobile present of 1949, in many ways, Kind Hearts and Coronets is all about this rigidity of class structures and what happens when you add ambition to the mix. (While it’s never explicitly mentioned, one character’s social climbing is charted by the increasingly absurd and elaborate hats she wears.)

Films of all genres were shot at Ealing before its acquisition by the BBC — horror, melodrama, war pictures, sci-fi — but the best remembered are all dark comedies… emphasis on dark. The Ladykillers (which also starred Alec Guinness) is about a group of hoodlums renting lodgings in an old lady’s cellar so that they can tunnel through to the vault of the bank next door; Passport to Pimlico features a group of Cockneys exploiting a geopolitical loophole to circumvent wartime rationing regulations in bombed-out London; Kind Hearts and Coronets is an affectionate portrait of a cold-blooded serial killer.

While it might be fair to say that for the past 30 or 40 years, much British film has been viewed largely as quaint, parochial, mannered and repressed (think of the award-winning films and box-office pleasers like The King’s Speech, the romantic comedies of Richard Curtis or Shakespeare In Love), but postwar British cinema was risqué by comparison with the US. In America, the Hays Production Code meant no swearing, no sex (especially no adultery), bloodless violence and above all, that crime should never be shown to pay. For this reason, British cinema of the late 40s and 50s represented permissiveness, licentiousness and subversion.

This meant, of course, that adjustments had to be made in order for its movies to be exhibited in the States — in numerous cases, nonsensical endings would be hastily shot and tacked on to cater for the more delicate sensibilities of audiences on that side of the Atlantic. Six minutes of Kind Hearts and Coronets was cut and ten seconds added to the end of the film (rather anticlimactically closing its deliciously ambiguous open ending) to comply with the Hays Code.

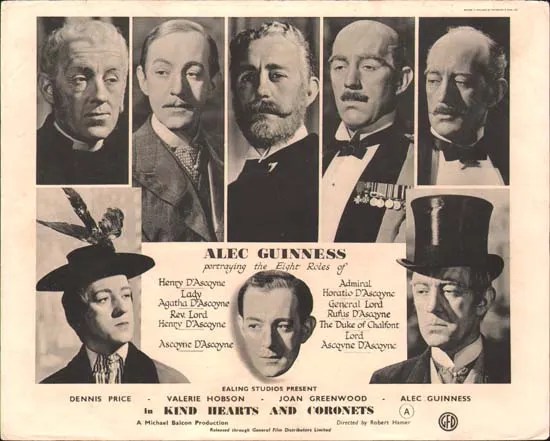

Alec Guinness was a superb performer, much admired as a comic and a dramatic actor (although, sadly, he is best remembered for playing Obi-Wan “Ben” Kenobi in the original Star Wars trilogy – a fact which rankled with the contemporary of Laurence Olivier, Oscar winner and Knight of the Realm).

The portrayal of eight different characters by the 34-year-old Guinness (the producers offered him four roles but he insisted on playing the entire D’Ascoyne family), ranging from 23-year-old naif Henry d’Ascoyne to a superannuated pastor to suffragette Aunt Agatha pamphleteering in her hot-air balloon, is as impressive technically as it was theatrically. In one scene, the six surviving D’Ascoynes are seen attending a funeral together. It took two days to film (much of that time spent waiting while Guinness underwent transformation in the makeup chair), with the camera mounted on a specially built platform to keep it as still as possible. Douglas Slocombe, the cinematographer, spent the night with the camera to make sure that nothing accidentally nudged it out of place. During the day’s filming, each of the characters was shot in turn and the film was then wound back for the next character.

Despite Guinness’s multiple roles, top billing in Kind Hearts and Coronets rightly goes to Dennis Price, who plays the antihero Louis. Price carries the film with effortless grace as he cheerfully cuts a swathe through the great and the good of British society. It’s a far less scene-stealing feat than Guinness’s, but in appearing in virtually every single scene and providing the narrative voice over (a trope that was popular at the time but usually confined to film noir, so itself an unusual choice for a comedy), his presence utterly permeates the entire film. Sadly, Kind Hearts and Coronets would be the pinnacle of his career. Handsome and talented but gay and closeted, Price died an alcoholic in his 50s. (Interestingly, like Louis’s mother, Price had aroused the displeasure of his people by becoming an actor rather than joining the army or the church as family tradition dictated.)

Joan Greenwood, portraying Louis’s childhood sweetheart and accomplice-after-the-fact, seems to relish her role as the coquettish Sibella. With her raspy, throaty voice and expressive mouth, she exudes sexiness throughout – and not always to her own advantage. Valerie Hobson as temperance advocate Edith D’Ascoyne is all moral rectitude and noblesse oblige, yet the character is anything but two-dimensional, exuding warmth and kindness despite her elevated status.

Leave a comment